Pasture rotation: making hay while the sun shines

As we approach the autumnal equinox, we begin our annual fretting about how long the pasture grass will last and when we have to convert to pricey hay feeding for the winter. The worry meter reads particularly high this year because much of the Pacific Northwest got far too little rain, so the demand for hay outstrips supply.

Short of taking the flock down the road to the knacker, we have few options for keeping the hay bill in check. Our most promising tactic is disciplined pasture rotation.

For the grass novice, pasture rotation is neither an astrological gimmick nor a game of chance. It refers to the notion of putting grass-eating livestock on very small portions of a pasture in succession so they will of necessity eat all the green stuff – grass and weeds alike – evenly and not move through the entire pasture all at one time, cherry-picking the tastiest new grass and leaving everything else to flourish in its place. Move the animals systematically, before they take the vegetation down too far, and each part of the pasture recovers nicely, ready for the animals again when the rotation starts a second time.

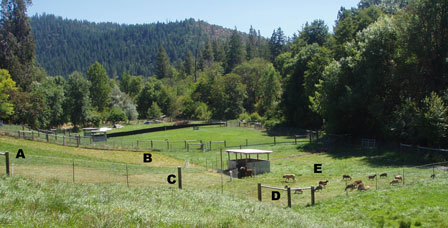

Let me illustrate. The following picture shows five sections of one of our pastures, labeled sequentially according to when the sheep first grazed on them in this rotation. Please bear with me in this labeling and description and I will do my best not to be unduly pedantic. Section “A” was the first section eaten, B the next place we moved the sheep to, and so forth.

The sheep are in section D, which still looks pretty green. They already have eaten, in turn, sections A, B, and C. When I took these pictures on August 24, the sheep had been on section D for one day. Mind you, there are over 50 sheep and two llamas, our adult Llucy and her cria Hank, eating this pasture. At least from a distance, section A, which they ate 7 or 8 days earlier, already is in pretty good shape, regenerating nicely. Section B doesn’t look very good in this picture, but take my word for it, it has turned over a new leaf or two. In fact, I will show you a closeup of section B in a minute to illustrate how much has regrown in just one week. Section C of course looks awful because the sheep have only been off it for a day or so. Section E, to which the sheep will be taken next, looks even better than a “last” section usually does because no sheep have been on it for several weeks while we worked other paddocks.

The downside to pasture rotation is that to make it effective, you need to enclose areas smaller than your instincts tell you or than you want to. Even more important, you need to move the sheep every 4 days. If you have the right sized group for the right sized area, the sheep should eat it down in those 4 days. Even if you guess wrong and all the grass has not been eaten down, you still need to take the sheep to the next area. Grass starts regenerating after 4 days and you must get those hungry mouths moved before they start eating the new growth. You can move the animals before all the grass is eaten, of course, but then you are not taking full advantage of your pastures, are you?

Here’s the good news: if you use something lightweight for your interior pasture dividers, it is really easy to move the sheep from one section to another.

Now let’s look at the same section of our fields from a different angle.

Areas A and E, where the sheep have not been for the longest time, are quite lush. The most recently-munched areas, B and C, are starting to recover. Area D is in the process of disappearing into rumina. And by the way, the far and near paddocks in this picture held a good portion of our flock about 3 or 4 weeks before this picture was taken. Recovered nicely, didn’t they?

What is amazing about pasture rotation is how effective it is, and how fast pastures recover in the summer and early fall if they are irrigated. Let me show you comparative closeups, actual photos with zero retouching and zero tampering from any photo software program. In the next picture, you are looking at section C taken with my zoom lens, the section the sheep left just a day or so earlier. From a distance, it appears a wasteland (look back at the first picture above), but look more closely and you will see a lot of live green grass shoots under the scruffy-looking stuff on top. Those shoots are healthy enough to start growing robustly again now that several dozen efficient mowers have moved on to greener pastures.

Truth to tell, Steve left the sheep on this section one day too long. Live and learn.

Next I want to show you what 5 or 6 days of recovery had done to section B by the time I photographed it on the 24th. First, look at this medium-range picture of section B, tucked between the “virgin” section E below and the first-eaten section of this pasture, section A up there in the left-hand corner. See how “hurt” section B looks from mid-range?

Now look at this same section B up close through my zoom lens. Again, absolutely no retouching and taken within minutes of the other pictures. Not bad recovery for land that had several dozen sheep on it just a few days ago, eh?

And finally, here is what the grass looked like up close in section E, where the sheep had not been for several weeks. Obviously it is the most lush, lots of high quality grass, lots of clover, pasture yearning for a bunch of cute little Soay mouths.

Because this is our first year of disciplined pasture rotation, it is too soon to know know how far we can extend the grass-eating season into the fall. For our large flock of about 130 Soay, every week we can keep them on grass and off hay saves us a lot of money, easily enough to get a shepherd’s attention. Even if we had a small flock, perhaps 8 -12 animals, the process of moving temporary fencing every few days would still be cost- and time-effective. Using the theory of compensatory cash flow, any shepherdess worth her salt can readily convert the savings into a weekly visit to the local spa, perhaps a leisurely pedicure, or something equally worthy.

As for how you divide up a large pasture area into the small sections required for effective pasture rotation, almost anything portable and capable of fooling the sheep into staying in one section at a time will work. The best and easiest setup uses three “sides” worth of divider material, one for the leading edge of the procession across the pasture, one for the trailing edge (so the sheep will leave the “used” section alone and let it recover), and a third one to create the new leading edge while leaving the current setup in place. You can do it with two pieces, but try persuading the sheep to wait in their well-worn section while you set up the yummy new one next door. Life’s too short.

If you happen to have a bunch of lightweight plywood panels, or sheep panels, or horse panels, you can string them together into dividers. Or you can do what we did, and spend part of the savings in hay costs to purchase three lengths of ElectroNet, a dandy product from Premier that is lightweight and effective. The amount of electricity it uses is miniscule, and it is remarkably easy to move around. It will not suffice as your permanent perimeter fence, because once in a while a determined Soay will simply walk through it and accept the electric shock, but since the animals get moved before they perceive themselves as starving, they generally do not want to escape. I have assigned myself the director of hay procurement so I can pilfer the remains of the savings for the aforementioned compensatory self-indulgence.

Before closing this interminable post, I have to boast a bit. I just went down to the fields to be sure the pasture featured in this recitation (South Cannon by name, but that’s a story for another day) still looks good. Wow! Have a look. The first of these “after” pictures was taken from the same angle as the first picture in this post. The second “after” picture shows the same area as the section B mid-range wedgie photo above.

Data report: (What, you thought the wife of the geneticist-turned-shepherd could get away with zero data in a post?) I took these pictures and their counterparts above 19 days apart. You can judge for yourself whether pasture rotation works.

Educational note: If you ever see a flyer announcing a pasture management seminar given by Woody Lane, by all means attend. We learned more about caring for our fields in a couple of hours with him than anything we had picked up from books. If you can’t find a Woody Lane seminar near you, here’s a link to an excellent summary of what he and others of his ilk have to say about pasture rotation and pasture management. For serious pasture managers, the bottom line is that we shepherds do not keep Soay for their fleece, their meat, their genetics, their attractive appearance as lawn statues, or their status as a rare and endangered breed — all attributes near and dear to a Soay breeder’s heart. To the contrary, sheep exist only as grass conversion machines. Not a bad way for all of us to think about our flocks, actually. If nothing else, it turns the beautiful fleece, tasty meat, and intriguing genetic puzzles into appealing bonuses beyond the core pasture rehabilitation function.

We are still experimenting with the right size for each section as we march the sheep across pastures of differing grass density and quality, but one thing we know already. To every field there is a season: turn – turn – turn.

For now …